“It’s not just the information that the letter conveys that’s important, but the fact that it is a letter.”

Hi everyone! It’s Sophie Spruce, editor of Pride and Possibilities, here with a very special edition on Regency letter writing. For this issue, I’ll be interviewing Barbara Heller, curator of a special edition of Pride and Prejudice: The Complete Novel, with Nineteen Letters from the Characters' Correspondence, Written and Folded by Hand and Eleanor Rust, who has a PhD in Classics and a research interest in 19th century women’s education and accomplishments.

Sophie Spruce: Welcome Barbara and Eleanor! Could you give a brief introduction of yourselves and what you do for our readers before we get started?

Barbara Heller: After college, I worked in and still work in film and television. I was initially a location manager, which is the department that finds all the apartments, restaurants, offices where scenes are shot, and it was really good training to try to find the location that furthered the narrative and visually helped tell the story. I feel this was perfect training for creating letters that gave as much information about the emotional state of the characters [in Pride and Prejudice] and who they are by their handwriting, their paper choice, how the words are on the page. Is it messy? Is it neat? Is it cramped? So, it all ties together: my bread-and-butter and my passion projects.

I was reading Pride and Prejudice, and I was savoring Mrs. Gardiner’s letter she writes to Elizabeth about Darcy’s involvement in Lydia’s wedding. I just love that letter because I imagine that I experience what Elizabeth experienced when she reads it. The shock of his role and being aghast and horrified and wonderous that he had to spend all that time with both Wickham and Lydia. And, of course, that he did it for her and there is hope of a future with him. Reading that letter, I thought “Wow, I would really like to have that letter.” I suddenly had this feeling of “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to hold the letter that Elizabeth Bennet received in my own hand?” And that was the genesis of then creating all the letters that are in Pride and Prejudice.

Eleanor Rust: I'm a long-time Jane Austen fan, and I love digging into the little details of Regency life embedded in her intricate novels. I was trained in academic research and writing in a different field, and now that I work in the corporate world I enjoy forays into Jane Austen's era as a hobby. I've focused mostly on the literature and material culture of women's accomplishments, so in addition to reading the same instructive books Austen or her heroines might have read, I've cut quill pens and written letters following their models. The deeper I got into the project the more I appreciated the detail and subtlety of Austen's writing!

Sophie: Wonderful! We are so glad to have you both for this month’s edition of Pride and Possibilities. Let’s get started!

Letter writing was a hugely important part of Austen’s world since it was the only form of long-distance communication at that time. So, what are some of the most important things to know about writing a letter in the Regency era, a brief overview before we get into more specific questions?

Eleanor: I think, to set the stage for all the details we’ll dig into later, it’s important to start with some of the limits that letter writers had to work with in Regency Britain. Postage was expensive and was charged by the miles a letter had to travel, and charges could be doubled if the letter included more than one sheet of paper! So, writers had to fit their messages into a single folded sheet that had to serve as the envelope as well. But within those confines, a letter was an object that could convey so much more than words— the writer’s choice of paper, handwriting, even how they folded and sealed the letter was loaded with social significance. If you look closely at how Austen describes letters written by Caroline Bingley and Mr. Darcy, for example, you’ll notice details that would have spoken volumes to her first readers.

Sophie: How were letters mailed? How long did it take a letter to be delivered?

Barbara: In Pride and Prejudice, there would have been an innkeeper in Meryton who also acted as a postmaster. The innkeeper would have a contract with the Royal Mail, and he would stamp any letters dropped off with “Meryton” and then mark it with dip pen, or quill pen. The Bennets would either have sent a servant to bring their mail or they would have a perk where the innkeeper arranged for the mail to be delivered and picked up.

I had always imagined Elizabeth waiting weeks and weeks for Mrs. Gardiner’s letter… but in fact, the Royal Mail in England had been overhauled and the mail was really efficient. Elizabeth probably had the letter from her aunt in only a couple of days.

Elizabeth’s reply to Mrs. Gardiner © Barbara Heller

Sophie: What would the cost roughly be? What actions would a person take to offset the cost of mailing a letter?

Barbara: Almost all mail went through London even if that wasn’t its final destination. The cost of sending a letter was paid by the recipient, not the sender, and it was based on the number of miles traveled and how many sheets of paper were used. A one sheet letter traveling under thirty miles cost about sixpence. So, a letter from Meryton to Mr. Collins at Rosings, which we know is roughly fifty miles would have cost sevenpence, equivalent today to roughly £2.5 or $3.13.

So, because it was expensive, people wrote in a very tiny hand so that they wouldn’t use a second sheet, and they would turn the paper and write perpendicular to the original lines. In Emma, Austen talks about how Jane Fairfax usually fills the whole page and then crosses half, although those lines were difficult to read. There were no envelopes as we know them. They wrote on the paper folded almost like a greeting card. Then the back was for the address, and they would write around the parts that were folded.

Example of cross writing

Sophie: So, we have the physical requirements of a letter as well as a brief overview of what the mailing system looked like. Moving on from that, I have a quote from Austen herself in a letter to Cassandra where she says, “I have now attained the true art of letter-writing, which we are always told is to express on paper exactly what one would say to the same person by word of mouth. I have been talking to you almost as fast as I could the whole of this letter." There was more to the art than just putting words on paper, right?

Eleanor: Austen is responding to advice in the conduct literature of her time, books with titles like The Polite Lady that told young genteel women that they needed to learn how to write letters in a natural, easy, but elegant style. They recommend picturing the recipient and writing the conversation you would have in person, just as Austen quips. Stiff formality was so last century, and the conversational style of writing was in, but those conduct books also recommend a long reading list of genteel published letters so you could absorb a good writing style!

Nervous writers looking for more practical advice on how to structure a letter or delicately approach a difficult topic could turn to letter writing guides with titles like “The Universal Letter Writer.” Typically, they include basic rules—like the correct title to use when addressing a letter to a baronet—and model letters on different topics like “adversity” and “courtship.” I like to imagine Mr. Collins copying out of those books!

Sophie: I know there was etiquette concerning who you could write to particularly unmarried men and women. Was there any other letter etiquette that needed to be followed? Was penmanship an important part of letter writing?

Barbara: Men and women couldn’t correspond if they weren’t engaged or married. Darcy hand delivers his letter to Elizabeth, and it was very improper of him to write her. If people had seen he had written her a letter, they would have assumed they were engaged. In Sense and Sensibility, Elinor assumes that Marianne and Willoughby are engaged because Marianne writes to him. So, [in Elinor’s mind] they have to be engaged. Otherwise, there’s no way Marianne would be writing to him because it’s such a huge breach of propriety.

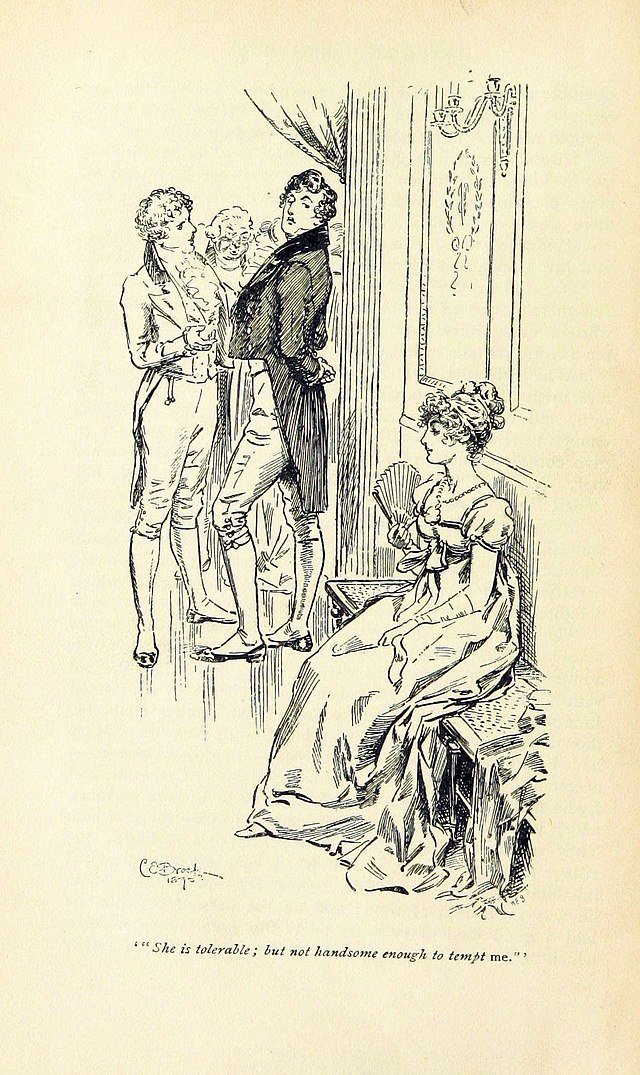

Illustration by Charles Edmund Brock (1870-1938) for Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1775-1817), public domain

Eleanor: Etiquette books of the time are full of rules, although most of them apply outside the family circle. For example, if you wrote to someone who was your social superior, you ought to get the best, most expensive paper and seal the letter with wax to show your respect. You were only supposed to stick your letter closed with a cheap paste wafer if you were writing to your family or on business. Austen’s surviving letters to her family show evidence of both kinds of seals, by the way.

Some unspoken rules seem to apply even among family circles, and one of those was to report and inquire about health and well-being frequently. When Austen (or her heroines) visited distant family and friends, the difficulty and expense of travel meant she would be staying away for weeks or even months, and in a time before modern medicine concerns about the health of loved ones were ever-present.

Elegant handwriting with a quill pen was an important basic accomplishment, especially for genteel women like Austen and her heroines. You would think that the wealthiest, best educated people would have had the best handwriting, but that’s not actually the case! Highly elegant writing in the style we now call copperplate was associated with the skilled tradespeople who wrote for their livelihood, like clerks and engravers, and some wealthy aristocratic men wrote with a lazy scrawl, simply because they could afford to be careless.

Sophie: Beyond the craft of letter writing, we also have letters as this form of reading material, not just an art form, but an ongoing conversation between two people. By this time, in the early 19th century, epistolatory novels have become a popular genre mainly due to Samuel Richardson who we know was a contemporary of Austen.

Austen also experimented in her early years with the epistolatory genre. It is assumed that the first draft of Pride and Prejudice, titled First Impressions, was written in the epistolary form. Even though that was then changed in the revision process, Austen keeps letters in the novel. In fact, there are nineteen letters, and they play an important part in Pride and Prejudice. You have Mr. Darcy’s letter to Lizzie, which is crucial to her character development and seeing Darcy as a romantic interest as well as Jane’s letter about Lydia which is the climax of the novel. Do you think this is a reflection of how important letters were in the Regency period?

Eleanor: Absolutely! The letters in Pride and Prejudice mark pivotal moments in the plot and major shifts in how Lizzie is thinking and feeling. We’re used to having the big news of our lives--- think a job offer, an engagement announcement, a death in the family--- come to us by phone, by email, text message, even Facebook status. But for people in the Regency period, any news that wasn’t delivered face to face came by letter. Letters could be life changing.

Barbara: I think what is really interesting about Darcy’s letter, which is the centerpiece of the novel, is that it is where Elizabeth has this epiphany and self-realization of how she’s completely misunderstood the situation. Darcy’s letter becomes a proxy for the man that Elizabeth is able to revisit and reread the letter in a way that if it was a conversation, she would be distorting it in her memory. But the letters on the page don’t change. That’s what slowly leads her to her epiphanies: reading and rereading the letter. The letter stays the same, but with every reading [Elizabeth] has changed. She can consider who Darcy is without his being present, without having to respond, without having to have a witty retort, and without any pressure to write him back. It’s not just the information that the letter conveys that’s important, but the fact that it is a letter.

Eleanor: Barbara has really captured all the nuances of Regency letter writing, so every element from paper to postmark matches the character and the moment in the novel. When I first opened the letters in Barbara's Pride and Prejudice edition, I felt like she made everything I'd learned about letter writing come to life.

Copy of Darcy’s letter to Elizabeth © Barbara Heller

Sophie: In the 21st century, letter writing is somewhat of a dying artform. This may be a strange comparison to make but since letters are a type of preserved communication it did make me think about emails and text messages. With emails, I was taught to write them as if I was following the same etiquette as writing a letter. I don’t know that emails are still taught that way, but for a long time, emails retained similar etiquette to letters.

Texts on the other hand definitely have more grey area to them, but there still seems to be certain rules on punctuation or using emojis. I was wondering if you think we have a modern day “letter” that might compare to communication in the Regency era or if it is an art form we’ve really seemed to lose?

Eleanor: There are still a few communication fossils in our lives that hark back to the letter-writing era, but it’s hard to think of great parallels! When I say fossils, I’m thinking about those ways that the letter format still persists. Like family newsletters at the holidays. I still get a few by mail, and more by email or social networks, but the format remains similar. Likewise wedding invitations, which often harken back to traditional styles of engraving and language and might still arrive by mail. Job cover letters are another fossil. I haven’t printed out and mailed one in well over a decade, but the job documents I send and receive over email look very similar to the format I was taught in high school.

It isn’t a perfect match, but email newsletters, as well as the blogs they have mostly replaced, remind me a lot of the epistolary format of Regency era writing. It wasn’t just novels that were written in the epistolary format! The Gentlemen’s Magazine, The Ladies’ Magazine, and other periodicals included what we would recognize as articles and essays, but a lot of the content was formatted as letters from readers and editors. It’s interesting that in some ways we’ve returned to a form of public writing that has letter-like qualities.

The connected prose of a letter written by a single writer to a single reader does seem to be fading away from our cultural radar, in favor of the more immediate conversational exchanges of text messaging and video calling. But whenever technology has changed how humans communicate, it’s never all at once or forever. In music, just think how popular vinyl records are, and I hear cassette tapes are next! I just learned about a correspondence club in my hometown that aims to encourage more letter-writing. I hand-wrote a letter to my aunt just last week. I’m not counting out letter writing yet!

Sophie: Awesome! Barbara and Eleanor, thank you so much for your time! I know I have learned more about what mailing and letter writing looked like in the Regency Period, and I’m sure our readers have, too.

© Sophie Spruce, with thanks to Barbara Heller and Eleanor Rust:

Barbara Heller’s career in film and television encompasses finding furnishings and props for many shows including The Americans and When They See Us; location managing films for Francis Coppola, Nancy Meyers, and Barbet Schroeder; and directing award-winning short films that have played at festivals around the world (Cannes, Berlin, Sundance). She graduated from Brown University with a degree in English Literature and lives with her son in New York City. Author of Pride and Prejudice: The Complete Novel, with Nineteen Letters from the Characters' Correspondence, Written and Folded by Hand.

Eleanor Rust earned a PhD in Classics before becoming a marketing professional in the music industry. Her life-long love of Jane Austen led her to explore early 19th century women’s education and accomplishments as a hobby. She co-hosts Frances Wright: America’s Forgotten Radical, a podcast about an Austen contemporary.

Join Jane Austen’s Family

Our annual fundraiser, the Jane Austen Parade for Literacy, is Sunday 23rd June at 1pm, and retraces Jane’s steps from her cottage in the middle of the village to Chawton House, owned by her brother, Edward Austen Knight. All proceeds to the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, Regency attire not essential.

Join over 120 individuals, book clubs, libraries and book shops that have signed up to host a Jane Austen Tea for Literacy. You’ll have fun with your friends and support literacy, imagine how good you’d feel!

You can make your party as simple or as fancy as you like. You can host in person or host a virtual party, throughout May and June (the Tea for Literacy website will stay open until end Sept if you want to host your party a little later in the year).

Sign up for FREE today get a FREE host kit with everything you need, including menu suggestions, games (Jane Austen and general themed), a video from Caroline Jane Knight (Jane Austen's fifth great niece) to welcome your guests, an ambient video and Spotify playlist, lots of Canva Tea for Literacy branded templates, easy ways to fundraise…..and much more.

Or, for an authentic Jane Austen Tea Party you can purchase The Complete Jane Austen Party Pack from our shop for a complete menu of recipes from the family that Jane would have eaten, and a pack of riddles and games mentioned in Jane’s novels and letters. Sign up as a Friend of the Foundation to receive The Complete Jane Austen Party Pack for free, and full access to all our community events, book club, reading challenges, giveaways and much more. For more information: Our Community — Jane Austen Literacy Foundation (janeaustenlf.org)

You'll get gifts from us to thank you for hosting and an invitation to attend an exclusive and private virtual piano concert with Jane Austen's family in July.

Register for FREE today and help children around the world learn to read and write.

Friends of the Foundation

Join our community as a Friend of the Foundation to support our literacy work. You’ll get access to all of the features, resources and exclusive events of the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation Community and you’ll get a vote in our book club pick every month. For information and to sign up, click below: